To Do or Not to Do, That is the Question

Every painter knows there are pros and cons to painting from a photograph, especially when painting a face or figure. Most master painters know beginners do not do so well, working from a photograph. Most know that the only way beginners get a good start is from a photograph. It’s the typical Catch 22 problem to solve when launching out into portrait painting.

With this in mind, I am writing this article: (1) to outline the opportunities one has in painting from a photograph or live model, the times one can choose, (2) to specify the times it is best to work from a model, (3) specify the times best to use photographic reference, (4) to list the obvious, as in times one can only work from a photograph, and (5) to point out photographic errors one should ignore and revisit. This will not be all-inclusive, I’ll tell you from the get-go. This will be an introductory pass at a a very deep subject. To be very fair, I must say that the masters prefer to err on the side of painting from life. This viewpoint is that of the Portrait Society of America with which I have been associated 8 years or more, including attending their annual conference.

This is the viewpoint of masters with whom I have contact, as well, such as Virgil Elliott, a master portraitist I met at the PSoA conference, who is a guru of oil painting and author of the textbook on completing portraiture entitled Traditional Painting, Advanced Techniques and Concepts from the Renaissance to the Present. Attach link to: www.goodreads.com/book/show/595646.Traditional_Oil_Painting.

1.Opportunities: Shall I get a live model, or use a wonderful photograph?

By far the best opportunities for working from a live model are in workshops where at least one day offers painting from a sitting model. These courses are usually week-longer’s and are very pricey. If you have chance and money, go for it once a year. Once you are home from the experience, write up everything you have learned. Teaching can be actively mined for decades afterwards, but it must be actively recalled and used to qualify.

Take your sketchbook with you everywhere you go. It helps to have a reputation as an artist to give you the nerve to whip out a sketchbook, but go ahead, and it will work both ways. Sketching will build your abilities and your reputation as an artist.

In portrait conferences like the Portrait Society of America’s annual which I have attended 7 or 8 times, topnotch models are hired for a multiplicity of the sessions, of which I take every single possible advantage, even the paint-out session at the beginning which has 6 to 8 models to choose from or change up and do quick sketches. You’re already paying, so get your money’s worth.

Harass your family when they are sitting or sleeping or doing any minimal activity that keeps them relatively still for a half hour or more by whipping out your sketch book and sketching them.

When no one presents themselves to your studio or your near presence, pull out a photograph, preferably one of your own, and go at it. You don’t have to have your $2-grand easel set up for this; one piece of hardboard will lean on anything and you can tape the photo to it. Have your sketch bag ready and filled up with pencil sets and watercolor tin.

2. Times Best to Work from a Model.

When you are doing a portrait, it is always advisable to invite the model in. I do this for startup sessions, at mid-point, and at the conclusion of the work. If the personage is retired or available for longer stints of time, by all means, set them up for 3-hour sessions. When you want a quick portrait, and you are working outside, pull in any willing body and start sketching with brush and paint. Always, if you can manage that, it is the preference.

3. and 4.Times to Pull Out the Old Photo.

* When the subject is dead (set up manikins to supplement).

* When the subject lives on another continent.

* When the subject lives too far away for frequent side trips.

* When the subject is a baby.

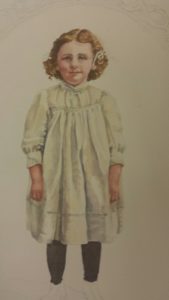

* When the subject is a wiggly child, especially a 2-year-old.

* When the subject always scowls and you have one photo with a pleasant look.

* When the subject is a nervous dog.

* When the subject is a racing horse.

* When you like. However, just know that it will only be as good as the amount of expertise you have under your best.

5.Photographic no-no’s, or what to avoid when using a photograph.

Using someone else’s photo without permission, unless you sign their name with a slash and your name on a non-commercial basis.

Using someone else’s photo even with permission in a juried art exhibit. The composition must be your own.

First,and most obvious in the list of what to avoid might be transcribing, or point-by-point transference of a photograph with a grid, like so many artists are taught to do. They always look fake and wooden to me. Unless the artist is already good at three-dimensional drawing, in which case, it could be stupendous (which means they really didn’t need it, anyhow, except as you would use a mirror or walk a distance away).

The second thing evolves out of this and would include distortions, especially those caused by foreshortening, as in when the face is nearly on top of the camera lens, or the subject is in a tree house and the foot is in your face nearly covering his whole figure, things like that. This might be a good opportunity to mention that I have a book on drawing faces in pencil. (

That leads to a third ‘no-no.’ Sometimes the most pleasant faces are smiling ones, and I have to slap myself every time to not paint a portrait with a grin in it. I know I mustn’t, but those snapshot moments just keep enticing me. I don’t have my fellow professionals’ love for lack of personality, the back of a head, the downcast look which I always suspect is because they can’t paint eyes very well. I prefer a model with a pleasant look, anywhere from a Mona Lisa smirk to a full inner smile. I have done a couple with big, toothy smiles, but then, I’ve learned how to paint teeth and want to show that off. Teeth are very telling in the likeness of a face and small differences are really big. Still, in the world of portraiture, teeth are best avoided.

Shadowing is another danger zone in photographs. Hard shadows should are the mark of a rank beginner who has not learned a shadow begins with a hard edge and slowly fades to nothing. One must really apply the Old Masters’ squint technique to gain a sense of proportion, based on knowing the 10-gradient gray scale and how to apply that to the shadows you see. Photographs flatten altogether which hardens shadows with lines which don’t exist. You must have learned how to grade a gradient shadow on round surfaces or do a cast shadow moving away from round surfaces. Shadows begin with a line and end with none, is just one for-instance. It is amazing how soft the shadow wrinkles on a 95-year old are. They are never the black lines which beginners pass off as being Old Masters when they are really New-Beginners-Without-Teachers’ looks.

Another insight I got in doing the last portrait of a no-longer-living person was in portraying flesh colors.  All colors translate into grey tones. These greys are frequently translated back from a photograph into colors containing blue or green, which darken areas more than they should. Going softer and pinker in flesh tones adds to the look of a living child. Key to this might be that red copies as black.

All colors translate into grey tones. These greys are frequently translated back from a photograph into colors containing blue or green, which darken areas more than they should. Going softer and pinker in flesh tones adds to the look of a living child. Key to this might be that red copies as black.

Cast shadows can also be a problem, as in just behind the subject on a wall. I find these best to avoid altogether, but if you must, do way less than you think is called for. Much more to be said, here, but–

Misinterpretation of light and shadow is the biggest of all problems, and can pop up anywhere to form an eye, a nose, or an ear incorrectly. There is no cure for this except years of formal training in how to draw the angles of the face, and how to create the correct perspective of a round object or a figure. The best reference book I have is one that shows the face from every possible angle, even up the nose. No one can memorize every possible angle of every possible figure as in a hologram. Light source is important, but tricky.

Proportional figures. There’s not much cure for this over wide acquaintance with figures. I think the cartoon book on Captain Marvel comics is one of the best self-help figure drawing books available, you just need to remember to give a real person the 5 or 6 heads and not the 8-3/4 heads that build a superhero. Photos run rampant all over figures and their proportionality, so accurate physiology is the only cure for this. Having said that, the individual anomalies must be considered. I remember arguing with a student who forgot her snapshot of her grandparents that ears didn’t exist on a cross line as low as the lips, but only to the nose. She insisted. When she brought the photo, boy was she right, and this was of course one of the very differences in the norm which achieved likeness of the pair. Yes, it was true for both of the grandparents. A good figure drawing book I have used in teaching classes is How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way by Stan Lee and John Buscema.

Odd coloring. Don’t insist on using odd colors that just happen in a photograph. For this, you really need familiarity with color, shading in color, and persistence.

Use the largest photo you can find or have made. If it is of a face, then the face should be 4 x 6 inches, approximately.

Use a pho to that has lots of detailed information in it, and not one that is so faded, all the tones are light.

to that has lots of detailed information in it, and not one that is so faded, all the tones are light.

In conclusion, I need to say that you have to use a photograph as though you were a detective. You search for the truth that lies within it. Knowledge plus experience plus training. You can’t get around it, and the smartest thing is not to try, but to avail yourself of practice from life and photos, training from a good teacher, a good self-help book in addition, and time to grow. Jump in wherever you will, but if you short-change yourself in any one of these four directions, you will in some way warp the art product you want perfect.

Learn more »