When to Use Photographs

Discussion abounds among portrait painters about the good-vs-bad points of painting from a photograph, as opposed to painting from a live model.

Painting from life brings clarity to just how soft the transitions within the face are, especially in the seamless contours of a baby’s face. However, even the folds of the wrinkles of a 95-year-old are soft. It clarifies the softness of the extreme edges, showing how they round into the light. However, painting from a photograph clarifies the absolute boundaries of eyes, ears, nose, hair, in a forever-fixed position. This brings resolution to many internal disputes the artist faces the moment she begins fixing lines on a piece of paper.

The problems with painting from life are in ever-changing lines and movements, left-right, up-down, and not having a head full enough of every angle and curve of a roundly 3-dimensional object. The problems with a photograph are many–distortions in the planes, misreading the data, not understanding the 3-dimensionality at any point along the way, interpreting light and shadows, and more.

Most veteran artists maneuver both paths.

So, when I received a request to paint a life-like portrait of a woman’s 50-year dead grandmother when she was a young child, I was not alarmed. I’ve had a lot of experience over many years in ‘reading’ photographs when I worked ten years as artist in a photographic studio enhancing portraits. So I had a wide acquaintance with old photographs and enhancing them, making the project only marginally intimidating. My emphasis with anything photographic is in making subjects jump off the page to greet you. And one fact alone ends the portrait painting discussion–if the subject is not alive, you don’t have any option other than using a photograph. My client wanted her own picture of her beloved grandmother, as another sibling owned the original one, because she had seen my work, and had concluded she would prefer a work of art rather than merely a photograph.

She lives in another state. She had visited my studio several times, however, visiting someone in the area and acquired one of my gel pen paintings. She had the vision for a piece of fine art, as well as a likeness.

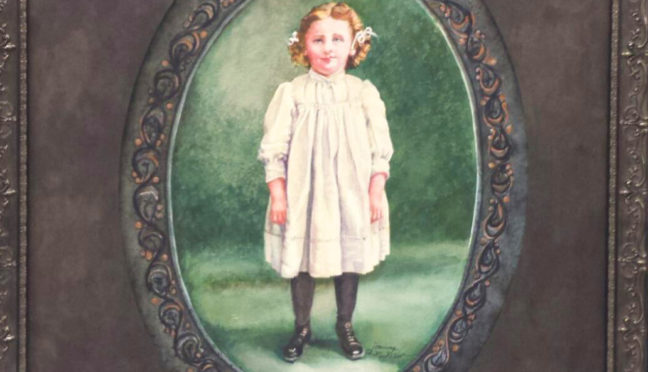

So, of course she wanted the feel and sense of an old photograph. Once our back and forth was firmed up, I received an 8 x 10 black and white with all the colors described to me verbally.

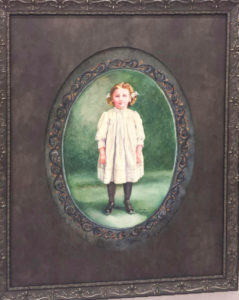

We discussed parameters, found samples and examples of the exact colors desired. Her color sense was exacting and precise, and her willingness to respect and work with me as artist was an artist’s dream. She wanted a certain finished size, so I had to work backwards in designing the figure in the space, allowing the amount of space for painting in what had been the original oval mat, the pattern on it, the actual matting, and the frame width. Every aspect of frame, mat, background colors, dress color, hair, eye, complexion color were described. We decided on watercolor paint as the medium to more accurately and sensitively express an old photograph. That meant bringing back all of the lost integrity of the image. If you have ever seen chalked-in old photographs, you probably know what I mean about so much detail having been lost.

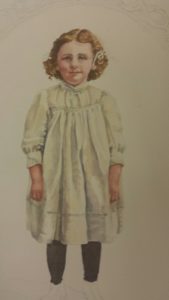

She sent me an 8 x 10 image of the original photograph, and my work began in earnest. I first drew many sketches of her on watercolor paper tinted yellow, the color of the dress. I drew her and re-drew her multiple times. In the end, I was not happy with the effect of the tinted paper, so I scrapped that version and began what would be the final on a 300# Arches cold press piece of watercolor paper, having acquired good practice in nearly memorizing her features one by one in every line variation. By this point, I had a decent hand-done oval. My drawing was nearing the ready phase.

Even then, I had to check and correct tiny little lines multiple times, moving them a hair up or down, a hair right or left. It was tedious work. Don’t ever commission someone who thinks their first line is final. However, extreme caution must be used in erasure, as well, as using the wrong eraser or overworking erasing can ruin a painting in short order, abrading even expensive 300# watercolor paper especially designed for watercolor abuse.

My biggest struggles, besides the hand-done oval, came in the colors, as the copy I had was black and white, and I had to dream up color mixes based on names of colors. I searched the web a lot for examples of ‘chestnut’ hair, and other descriptions. However, it was not my ignorance, but my knowledge that lead me astray. Knowing there is a lot of blue in a shadow color (for which I substitute green added to red to get the perfect complementary), I ended up with more shadow versions of the colors in her face than I needed. Then my client shared a painting she had bought that reminded her of someone in their family, sent me a picture of it, and I freshened up the facial colors using those. Don’t trust someone to do a watercolor portrait who says you can’t tinker with watercolors, either. You just have to know how.

A friend at one point made crucial comments that lead to change and downplaying some detail to greater effect.

At this point, the client preferred to be surprised, so the finished product was taken for its framing, a suitable  was picked, along with a mat that made the unit hang together in a way that seemed inevitable, as if it had always existed. The prince of all boxes was ordered at a princely price, and the work was sent off in fear and trembling through my favorite service who picks it up at my studio. Then I followed it on pins and needles until it was received.

was picked, along with a mat that made the unit hang together in a way that seemed inevitable, as if it had always existed. The prince of all boxes was ordered at a princely price, and the work was sent off in fear and trembling through my favorite service who picks it up at my studio. Then I followed it on pins and needles until it was received.

Finally the longed-for response arrived. “I can’t begin to tell you how ‘over-the-moon’ I am with my grandmother’s portrait!” was the first line in my thank-you letter from my client. Imagine my joy when she told me that the grandmother that was always in her heart was now in her home, too. And the very best thing a portrait artist can ever hope to hear, “You nailed it, girlfriend!”

Sigh. Now I can proceed to my next project. But first, this just came in from my client, “Oh, yes, tell Joanna she has my grandmother’s eyes down perfect. They’re the same as I remember!”

Learn more »

![541886_10151867873104694_1243631060_n[1]](https://joriginals.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/541886_10151867873104694_1243631060_n11-300x168.jpg)

![1175134_595792013806191_1972117313_n[2]](https://joriginals.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/1175134_595792013806191_1972117313_n2-300x216.jpg)

![1378769_606341199417939_456327840_n[2] - Copy](https://joriginals.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/1378769_606341199417939_456327840_n2-Copy.jpg)

![541886_10151867873104694_1243631060_n[1]](https://joriginals.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/541886_10151867873104694_1243631060_n1-300x168.jpg)

![1175134_595792013806191_1972117313_n[1]](https://joriginals.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/1175134_595792013806191_1972117313_n1-168x300.jpg)

![1002335_581905468528179_106879984_n[3]](https://joriginals.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/1002335_581905468528179_106879984_n3-300x113.jpg)

![1098305_586382878080438_1748309898_n[1]](https://joriginals.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/1098305_586382878080438_1748309898_n1-168x300.jpg)